Rishi Sunak says we are facing a “deep economic crisis”. Big words, not to mention depressing. But do they really add up?

Is Britain really facing something unique? Can he really blame this (as his speech suggests) on his predecessor? Or is something else going on?

Let’s start from the beginning.

There is no doubt that the UK is going through tough economic times right now. It is quite plausible that we are in the teeth of a recession. Look at indicators like S&P Global’s purchasing manager index — a measure of how things are going now — and it’s contraction territory. It’s a recession warning, and it’s not a mistake.

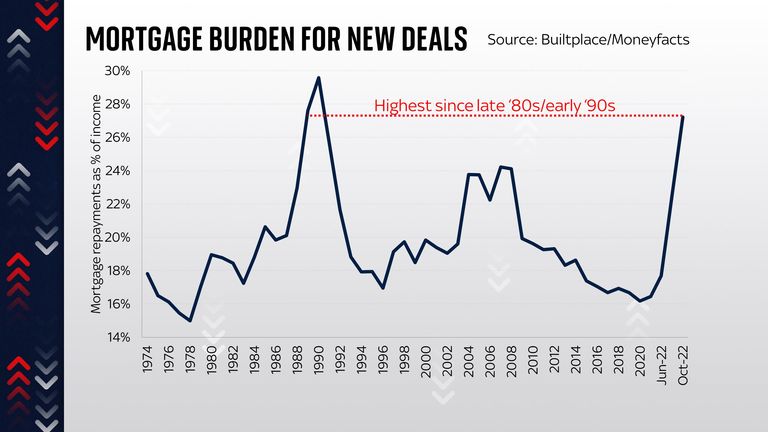

And there are certainly some factors that will make this a bleak year or two for households. For one thing, mortgage costs are rising, and rising fast. The average two-year fixed-rate mortgage rate is now over 6%, marking the highest repayment rate as a percentage of household income since the late 1980s or early 1990s. This is clearly not good news.

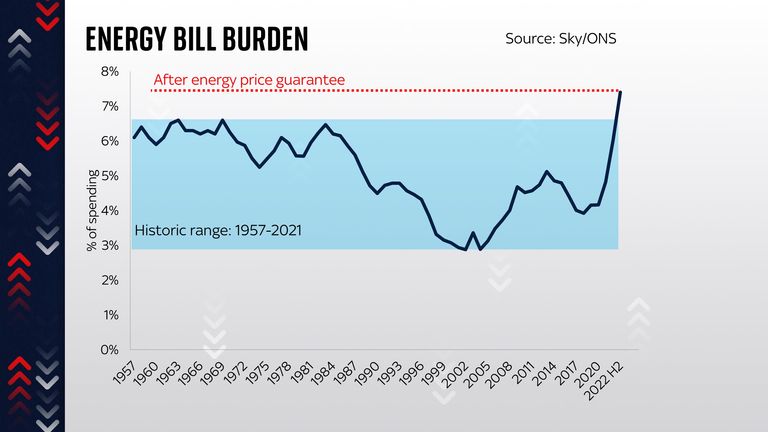

And it’s a similar story with electricity bills. Even allowing for the energy price guarantee introduced by Liz Truss, the amount the average household spends on energy this winter will still be the highest we have seen since at least the 1950s. Again, this isn’t great news – and note that as the scheme has been shortened from two years to six months, it’s likely that costs are even higher next year.

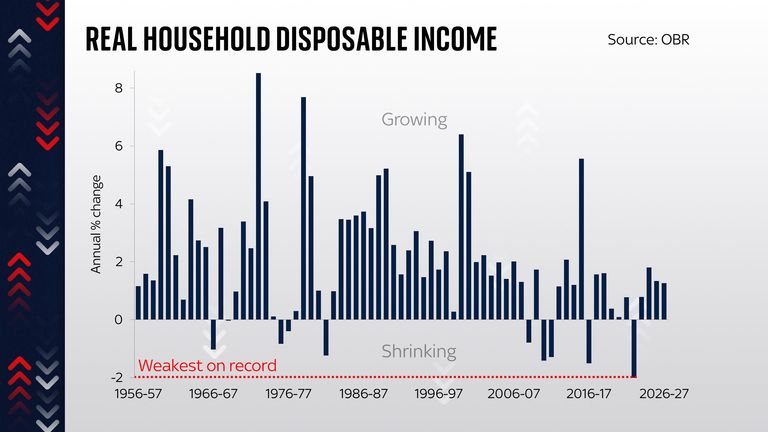

Taken together, any measure of our overall standard of living points to a staggering drop this year. We will all be much poorer compared to what we normally want to spend our money on. And this is largely due to the impact of higher energy prices that permeate all areas of our lives.

But these are not the only problems facing the government.

The UK is not the only major economy facing a possible recession

One problem that no previous prime minister has been able to successfully address is declining productivity in the UK. Hourly productivity is perhaps the most important measure of our economic well-being, and since the financial crisis it has essentially declined, worsening (and this is no exaggeration) everything: our incomes, quality of life, tax levels and national debt.

And that’s before considering the deeper problems facing the global economy right now. The most obvious thing is that we are in the early stages of a new Cold War that could lead to trade blocs rather than a fully globalized world. And this forecast, frankly, is more optimistic than many. This will have huge economic consequences.

But here’s the thing. None of these problems are necessarily unique to the UK. The UK is not the only major economy facing a potential recession, with other European countries likely to experience even deeper cuts this winter. Disappointing performance is something that many advanced economies struggle with. Interest rates are rising everywhere (even if the recent increase in borrowing costs in the UK has outstripped other countries).

Many of the current problems predate the Liz Truss

Nor is it very fair to blame all these problems on Liz Truss: almost all of them predate her. And here’s what’s really interesting: the spike in government bond yields that followed her and Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-budget has now all but been erased.

Those gilded crops are now almost back to their former levels. So are expectations for Bank of England interest rates next year. This is an extraordinary turn – a consequence of the fact that the Rabbit government is no more.

Click to subscribe to Sky News Daily wherever you get your podcasts

But this means that in reality, much of the damage has now been erased. It’s worth thinking about for a moment. Remember: Rising yields on gilts, as international investors looked askance at the UK, pushed up the potential cost of borrowing for both households and governments. This meant that if the government continued to issue debt at such interest rates, the interest on the debt would be much higher. The IFS has estimated ongoing costs at around £10 billion a year. This is a big deal.

The “confidence premium” on government debt is shrinking

But now that the “confidence premium” on government debt is shrinking, that problem is no longer an issue. Perhaps soon he disappeared completely.

It begs the question: Why did Rishi Sunak try to create such a somber mood on the steps of Downing Street? I suspect it’s about 60% politics and about 40% economics.

Politics first: if he can convince the public (and his MPs) that things are bleak, it means less resistance to the inevitable cuts. As much as Covid has united the party, perhaps he believes, the threat of economic contagion could do something similar.

If he can convince the public that the bad news he is reporting is about Liz Truss and not about his own policies as chancellor (most of these problems were problems when he was in Downing Street in charge of making sure something to do with them), then it’s good that it will obviously suit him. Even if it’s not entirely accurate.

Sunak’s warnings are only 40% of the economy

The 40% economy is intriguing because there is a virtuous circle here. If he can use phrases like “deep economic crisis” and “difficult decisions”, he will be able to convince the markets that he is really serious about debt reduction, which in turn should push gilt yields even lower. This means that the hole in the public finances is also suddenly smaller.

The tough talk may actually mean he doesn’t need to be so tough in the upcoming mini austerity budget or whatever we’ll call it.

Not too much of that will be revealed when the fiscal report comes out. It is clear that we are in for severe cuts in the economy. But most of the problems they have to deal with arose long before Liz Truss got to Downing Street.

https://news.sky.com/story/why-is-rishi-sunak-casting-such-a-sombre-mood-its-more-about-politics-than-economics-12730054